Limitless obstacles confronted with tireless imagination.

Pioneers, when and wherever they may be found, share certain qualities. They tend to be self-confident, visionary, determined, and not easily dissuaded by the doubts of others. George Washington Bush, the first settler in Washington Territory, arrived at Bush Prairie at the southern end of Puget Sound in 1845. By the early 1850’s, encouraged by the promise of the Donation Land Act (and, for some, the disappointment of California gold), a few hardy souls were scratching out an existence and “proving up” their claims on the Olympic Peninsula.

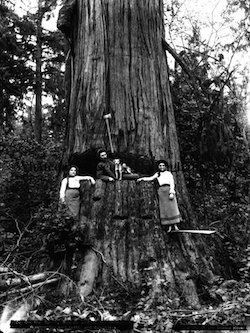

Whether or not these early pioneers intended to be loggers, they quickly became accustomed to the axe, saw and springboard. The forests that they met head on stretched from the alpine peaks to the seashore. Diaries of that time preserve the common lament that with one foot in the boat and the other in the forest, they met their dream first hand.

There were few harbors and an abundance of rocky headlands. Most pioneers sought river deltas and moved up river in search of open meadows where nature had opened a foothold in the formidable forest. The one resource they needed—wood&mdashwas, by any measure, abundant. But was in such robust form as to be mocking in its stature. Even with the help of the few others available, cutting trees a dozen or more feet in diameter to manageable, if not yet useable size, was daunting.

There were few harbors and an abundance of rocky headlands. Most pioneers sought river deltas and moved up river in search of open meadows where nature had opened a foothold in the formidable forest. The one resource they needed—wood&mdashwas, by any measure, abundant. But was in such robust form as to be mocking in its stature. Even with the help of the few others available, cutting trees a dozen or more feet in diameter to manageable, if not yet useable size, was daunting.

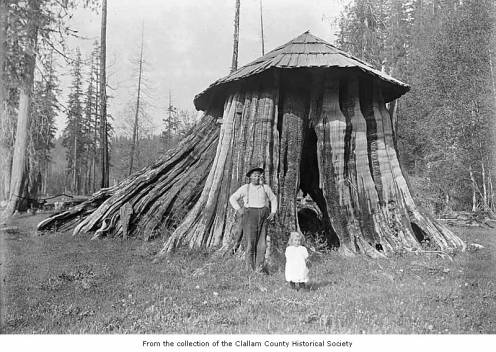

Having felled the trees, these land warriors gained sunlight. But what to do with the stumps that barred the progress of agriculture? Most were burned in place and more than a few became a pioneer’s home. One in the Elwha Valley served as a Post Office from 1891 until the early twentieth century. (Click on image to view original.)

Every river and many major streams were host to these pioneers. A few “proved up” and a few of those claims remain within the descendent family today, attested to by signs declaring the enduring spirit of those who led the way. For those who gave up, it was less a lack of effort and more a deserved distaste for a constant diet of potatoes, sauerkraut, and venison; grueling hard work; and a climate long on cold forms of moisture and short on warming sun. If the soils weren’t thin and acidic they were often overgrown with ferns whose roots posed a major obstacle to farming.

On the Sequim Prairie grazing was possible in part due to the burn management practices of the indigenous S’Klallam tribe. President Andrew Jackson signed John W. Donnell’s Homestead Act claim patent in 1866 making him the first settler on the Sequim prairie. (See City of Sequim – 1800’s to early 1900’s.) Others soon flowed on to the prairie as did water, in 1896, via the first of several irrigation ditches. Crops and dairy cows grew to economic prominence and peaked in the first half of the 20th century. Cows gave way to cauliflower and root veggies, and then to retirees. Today less than half a dozen dairy farms remain. Producing forty percent of the world’s hybrid brussels sprouts and cauliflower seed, as well as organic seeds and produce, land use has been transformed. Residences, for the highest concentration of retirees in the state, compete with farmland, threatening to irrevocably alter the nature of the community.

Making do with what they had, producing what they could, and always seeking the proverbial road to market—these were the three legs of the pioneering stool. Those who found all three prospered and those who didn’t worked for those who did, or moved on. Trading in “Indian” goods and contraband whiskey showed up early in the transition from pioneers to settlements, and transportation hastened the change.

The first settlement on the Olympic peninsula was at New Dungeness, established in 1851 by B.I. Madison and D.F. Brownfield. The Homestead Act of 1862 reinitiated free claimable land on the peninsula. Those without the means to own the timber sought employment from those who did. Timber camps and saw mills helped those “proving up” their claims by providing supplemental income. Wives and children were commonly left on the claim to satisfy the “continuous residency” requirement while men sought winter work where they could find it. Saw mills sprang up, first where ports and shipping existed and eventually where roads and rail could service the need. The peninsula saw hundreds of miles of rails laid in the 1870s and 80s; all of it gone today. Rails were laid, used and removed for reuse after an area was logged-out. Pioneer recycling anyone?

Regardless of origin, trade, craft or skill, married or single, these pioneers – like all others – met life head-on at the margins. Some succeeded, some failed, but most left their mark on a wild and untamed land, leaving the product of their imagination’s labor for those who followed in pursuit of the dream.

Notable among Olympic pioneers are:

- Huelsdonk, John (Iron Man of the Hoh) and Dora

- Humes Ranch

- Thomas Theobald Aldwell

- Bear Creek Homestead History

- Francis William Pettygrove

- Charles Mitchell, Slavery, and Washington Territory in 1860

A comprehensive look at the time and its people on the Olympic Peninsula, these web sites are well worth examining:

For a list of Clallam County’s pioneer families look here.